Welcome to My Learning Journey

Over the course of several weeks, a mixed-methods action research study was conducted to investigate how educators perceive and implement culturally responsive, multimodal, and inclusive instructional practices within a diverse urban K–12 context. Guided by the foundational work of culturally responsive pedagogy (Gay, 2018; Ladson-Billings, 1995) and Universal Design for Learning (CAST, 2024), the study drew on survey data, a semi-structured interview with an experienced educator, and systematic cross-analysis of qualitative and quantitative findings to identify conditions that promote, and those that constrain, equity-driven instructional design.

Although the initial focus centered on technical components of co-teaching and UDL, consistent with established literature on shared instructional responsibility (Friend & Cook, 2017; Murawski & Swanson, 2001), the inquiry ultimately revealed a broader set of interconnected themes related to identity, belonging, student voice, and collaborative classroom culture. These emerging insights aligned with sociocultural learning theory, which emphasizes the role of community, discourse, and relationship-building in academic development (Vygotsky, 1978; Hammond, 2014).

The following blog synthesizes the study’s central findings, integrates visual representations of the data, and offers evidence-based recommendations for curriculum development and instructional practice. These recommendations reflect current research on inclusive design, culturally grounded pedagogy, and teacher learning systems that sustain equitable outcomes for diverse learners (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017; Desimone & Garet, 2015).

What Numbers Revealed: Teachers Believe in Inclusive, Multimodal Practice, But Need More Support

As illustrated in Figure 1 (Bar Chart of Survey Item Means), teachers strongly endorsed key instructional practices associated with equitable and inclusive learning environments. The highest-rated domains included multimodal instructional design (M = 4.50–4.75), UDL-aligned strategies that address learner variability (M = 4.50), and frequent use of formative assessment to adapt instruction responsively (M = 4.50). Educators also reported consistent use of culturally responsive examples to strengthen relevance and engagement (M = 4.25) and indicated positive implementation of co-teaching models, including parallel, team, and station teaching (M = 4.25).

These patterns align with existing research demonstrating that multimodal and UDL-informed frameworks expand access to rigorous content, promote engagement, and support diverse learners (CAST, 2024; Gay, 2018). In other words, teachers in the study not only value these approaches but also view them as essential components of high-quality instruction.

However, Figure 1 also highlights a striking contrast. Educators’ perception of having adequate planning time and administrative support was the lowest, by a significant margin (M = 2.50). This structural limitation—echoed repeatedly in the qualitative data—emerged as a central barrier to implementing inclusive practices consistently and with fidelity. The findings suggest that while teachers possess the knowledge and commitment to design equitable learning experiences, the absence of sufficient time, collaborative structures, and coordinated leadership support constrains their ability to operationalize these practices effectively.

What Teacher Experience Revealed: Identity, Community, and Culture Drive Deep Learning

"When classrooms honor identity, invite students into dialogue, and integrate multimodal pathways for learning, they foster the conditions in which all students can not only engage but excel."

A Veteran Teacher

One of the richest components of this project emerged from a conversation with a highly experienced teacher whose insights illuminated the story behind the quantitative results. While survey data revealed clear trends in teachers’ valuation of inclusive practices, her lived experiences added nuance, depth, and contextual meaning to those findings (see also Darling-Hammond et al., 2017).

She spoke extensively about the role of identity-affirming teaching, emphasizing that learning begins with who students are, not solely with what they are expected to master. This perspective aligns closely with foundational research in culturally responsive pedagogy, which asserts that students’ languages, cultural histories, and lived experiences must serve as essential entry points for meaningful learning (Gay, 2018; Ladson-Billings, 1995). In her words, “Students need to see themselves before they can see the curriculum.”

Her examples demonstrated the power of such an approach. When students engaged in activities such as creating bilingual digital stories, connecting literature to personal or family experiences, or sharing cultural traditions, their engagement deepened and their learning took on greater relevance—an outcome well documented in the literature on culturally grounded instruction (Hammond, 2014; Ladson-Billings, 1995).

She also underscored the importance of multimodal strategies, explaining how visuals, modeling, hands-on activities, and digital tools help remove barriers and create accessible pathways for students to demonstrate understanding. This view is consistent with principles of Universal Design for Learning, which promote multiple means of representation and expression to support learner variability (CAST, 2024). For this teacher, technology was not an add-on or distraction; instead, it was intentionally selected to amplify student voice and support diverse learning needs (David & Weinstein, 2024).

Another theme that emerged was the centrality of community. She highlighted the value of collaborative routines, restorative conversations, and culturally grounded norms that help students feel emotionally safe as they take academic risks. These practices echo research showing that strong relationships and predictable structures foster both engagement and higher-order learning (Hammond, 2014; Vygotsky, 1978).

What stood out most was how seamlessly her instruction blended high expectations with humanity. Her stories reinforced a core insight of this study: when classrooms honor identity, invite students into dialogue, and offer multiple modalities for learning and expression, students do more than participate—they thrive (Gay, 2018; Darling-Hammond et al., 2020).

What It All Means... Recommendations for Designing Curriculum that Serves Diverse Learners

Designing instruction for today’s diverse classrooms requires approaches that are culturally grounded, cognitively rigorous, and intentionally inclusive. The following research-aligned recommendations synthesize the key insights that emerged across quantitative findings, qualitative teacher perspectives, and the broader literature on culturally responsive pedagogy, UDL, co-teaching, and restorative practice.

A. Build Identity-Affirming, Culturally Responsive Curriculum

Instruction should reflect students’ cultural identities, languages, and community experiences, as culturally responsive pedagogy supports belonging and engagement (Gay, 2018; Ladson-Billings, 1995). Selecting representative texts, inviting student cultural knowledge, and using discussion protocols that foster empathy and inquiry help position students’ experiences as academic assets (Hammond, 2014).

B. Use UDL and Multimodal Principles

UDL and multimodal strategies ensure that learning is accessible through varied representations and expressions (CAST, 2024). Visual supports, multilingual scaffolds, flexible demonstration formats, and moments of student choice enhance agency and deepen conceptual understanding (Meyer et al., 2014).

C. Strengthen Co-Teaching With Structured Planning

Effective co-teaching relies on shared planning, clear instructional roles, and intentional use of models such as station, parallel, and team teaching (Friend & Cook, 2017; Murawski & Swanson, 2001). Digital collaboration tools can support joint planning and differentiation, especially when time and structure are provided (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017).

D. Prioritize Community and Restorative Practices

Emotionally safe classrooms promote engagement and support culturally and linguistically diverse learners (Hammond, 2014; Vygotsky, 1978). Restorative circles, co-created norms, and collaborative routines foster empathy, cooperation, and positive relationships, strengthening students’ readiness for rigorous learning (Vaandering, 2010).

E. Integrate Technology Purposefully

Technology should amplify learning, not replace it. Tools that support collaboration, creation, and accessibility, as opposed to passive consumption—align best with research on effective digital integration (Koehler & Mishra, 2008; David & Weinstein, 2024). Ensuring translation, captioning, and text-to-speech features further supports diverse learners.

Action Research Findings Video

To complement the written synthesis of this study, the following audiovisual presentation offers an overview of the action research findings and highlights key insights that emerged across the quantitative and qualitative data. This short video distills the major themes from the survey results, teacher interview, and instructional analysis, and visually illustrates how culturally responsive teaching, multimodal learning, UDL principles, and collaborative structures work together to support equitable classroom environments. The presentation serves as an accessible summary for educators, leaders, and community members seeking to understand the study’s core implications and the evidence guiding the recommendations that follow.

UNESCO’s Four Pillars of Education — and How They Strengthened My Understanding of Teaching and Learning

UNESCO describes education as far more than the transmission of knowledge (Delors et al., 1996). It is a human-centered, lifelong process built on four essential pillars: learning to know, learning to do, learning to be, and learning to live together. As my research unfolded, these pillars became a powerful lens for understanding what culturally responsive and inclusive teaching truly requires.

Learning to Know- Cultivating Curiosity and Deep Understanding

TThis pillar highlights the importance of helping learners develop the ability to think, question, and make sense of the world rather than simply take in information. Its focus aligns naturally with multimodal and UDL-informed instruction, which offer students multiple ways to engage with content. When learning is presented through varied pathways, students do more than recall facts; they actively build understanding in ways that reflect their identities, languages, and individual learning needs.

Takeaway: Students learn best when instruction is flexible, accessible, and rooted in meaningful inquiry.

Learning to Do- Applying Knowledge Through Action, Creation, and Collaboration

UNESCO emphasizes that education must equip learners to apply their knowledge in meaningful ways—to solve problems, collaborate effectively, and think creatively in diverse contexts. This pillar is reflected in instructional practices that make purposeful use of technology, incorporate hands-on learning tools, and design tasks that require students to create, analyze, and engage with authentic, real-world challenges. Through these approaches, learners move beyond passive participation and begin to demonstrate their understanding in ways that are active, applied, and intellectually demanding

Takeaway: Rigorous instruction is active, hands-on, and designed for students to practice real-world thinking

Learning to Be- Supporting Identity, Agency, and Emotional Growth

Learning to Live Together- Building Empathy, Respect, and Community

This pillar centers on the development of the whole person, identity, self-awareness, confidence, and emotional resilience, and aligns closely with identity-affirming approaches to curriculum and instruction. When students see their cultures, languages, families, and lived experiences reflected in the classroom, they are more likely to feel a sense of belonging and develop academic agency. Educators in the study demonstrated this by inviting student voice, valuing personal and cultural narratives, and fostering learning environments where mistakes were normalized and growth was celebrated, thereby strengthening both emotional well-being and engagement in rigorous learning..

Takeaway: Students flourish academically when they feel seen, valued, and empowered.

Perhaps the most relevant pillar for today’s classrooms, this principle underscores the role of education in nurturing cooperation, empathy, and peaceful relationships. This emphasis was reflected in accounts of restorative circles, collaborative routines, and culturally grounded norms that supported students in understanding one another and resolving conflict constructively. Such practices extend far beyond classroom management; they are foundational to creating inclusive, rigorous learning environments in which all students feel safe contributing their voices and engaging meaningfully with their peers.

Takeaway: Classrooms thrive when community, dialogue, and empathy are intentionally built into daily practice.

Culturally Responsive Practice– Research-Based Infographics

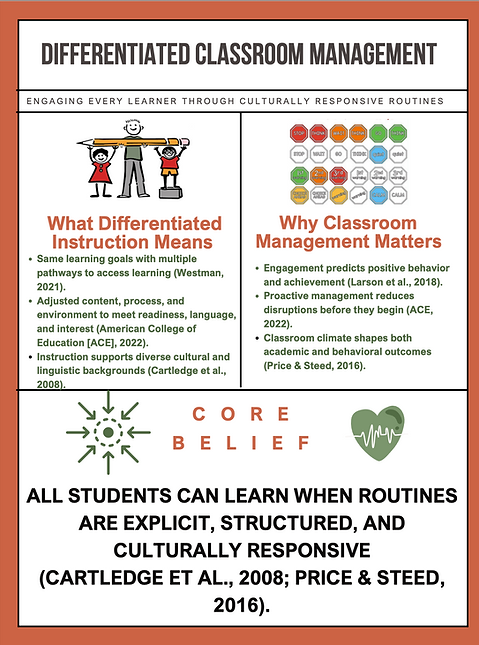

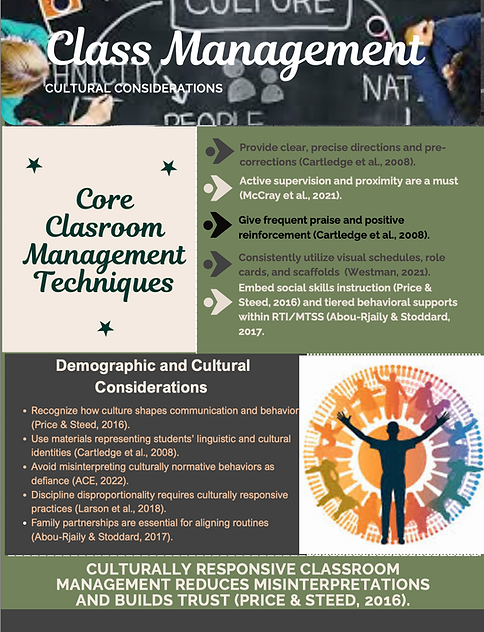

The infographics below offer an easy-to-read snapshot of some of the key ideas behind culturally responsive and differentiated classroom management. They highlight strategies supported by research—such as using clear routines, visual supports, culturally relevant materials, and proactive approaches to behavior (Cartledge et al., 2008; Price & Steed, 2016).

You’ll also see visual contrasts between what works and what doesn’t for diverse learners, as well as reminders about the role of teacher reflection and schoolwide support. Together, these graphics help bring the research to life and show how small, intentional shifts can create more inclusive and engaging classrooms for every student

References

Abou-Rjaily, K., & Stoddard, S. (2017). Response to Intervention (RTI) for students presenting with behavioral difficulties: Culturally responsive guiding questions. International Journal of Multicultural Education, 19(3), 85–108. https://doi.org/10.18251/ijme.v19i3.1227

CAST. (2024). Universal Design for Learning guidelines version 3.0. http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Cartledge, G., Singh, A., & Gibson, L. (2008). Practical behavior-management techniques to close the accessibility gap for students who are culturally and linguistically diverse. Preventing School Failure, 52(3), 29–38. https://doi.org/10.3200/PSFL.52.3.29-38

Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B., & Osher, D. (2017). Science of learning and development: Implications for education. Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2018.1537791

David, S., & Weinstein, H. (2024). Technology, equity, and purposeful design in K–12 learning environments. Journal of Digital Learning Research, 12(1), 45–62.

Desimone, L. M., & Garet, M. S. (2015). Best practices in teacher professional development. Phi Delta Kappan, 96(8), 40–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721715583955

Friend, M., & Cook, L. (2017). Interactions: Collaboration skills for school professionals (8th ed.). Pearson.

Gay, G. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice (3rd ed.). Teachers College Press.

Hammond, Z. (2014). Culturally responsive teaching and the brain: Promoting authentic engagement and rigor among culturally and linguistically diverse students. Corwin.

Koehler, M. J., & Mishra, P. (2008). Introducing technological pedagogical knowledge. Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465–491. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312032003465

Larson, K. E., Pas, E. T., Bradshaw, C. P., Rosenberg, M. S., & Day-Vines, N. L. (2018). Examining how proactive management and culturally responsive teaching relate to student behavior: Implications for measurement and practice. School Psychology Review, 47(2), 153–166. https://doi.org/10.17105/SPR-2017-0070.V47-2

Meyer, A., Rose, D. H., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal design for learning: Theory and practice. CAST Professional Publishing.

Murawski, W. W., & Swanson, H. L. (2001). A meta-analysis of co-teaching research: Where are the data? Remedial and Special Education, 22(5), 258– 267. https://doi.org/10.1177/074193250102200501

Price, C. L., & Steed, E. A. (2016). Culturally responsive strategies to support young children with challenging behavior. Young Children, 71(5), 36–43.

Vaandering, D. (2010). The significance of critical theory for restorative justice in education. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 32(2), 145–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714411003799165

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Westman, L. (2021). What differentiated instruction really means. Educational Leadership, 79(1), 71–78.